A new study published in Nature Communications presents a theory of how the brain can learn complex temporal patterns such as speech, music or movement.

The work introduces a framework describing how networks of cortical neurons can use local, real-time signals to recognise patterns that unfold over time, helping bridge a gap between neuroscience and machine learning. Beyond advancing our understanding of brain function, the findings could also inspire new generations of energy-efficient artificial intelligence systems.

In today’s artificial neural networks, learning temporal patterns – patterns that only become meaningful when observed over time, such as spoken words or music – typically relies on a method called “backpropagation through time” (BPTT). In this approach, the network’s activity is recorded while a sequence is processed and then replayed backwards in time while adjusting network parameters. While highly effective in machines, such a mechanism has long been considered biologically implausible: the brain cannot store detailed activity traces and replay them in reverse, and individual synapses only have access to information from nearby neurons.

“We now beg to differ”, says Paul Haider, one of the lead authors of the recent study. ”Our work shows how deep cortical networks could approximate BPTT in real time, without any backward replay of activity.”

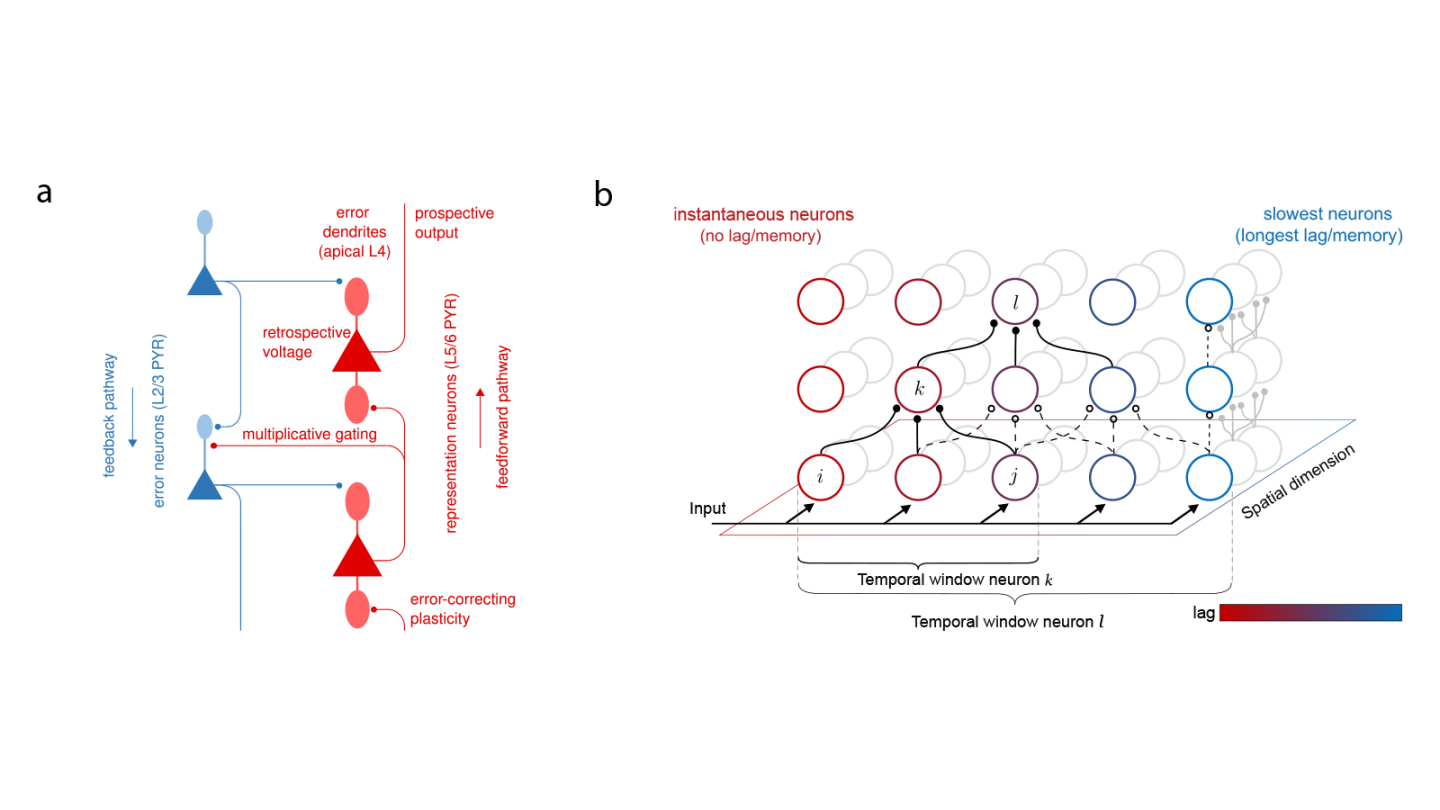

The key insight lies in a property of cortical neurons that has received little attention so far: their ability to anticipate their own near-future output. By combining information about the present with predictions of what is likely to happen next – a mechanism the authors call “prospective coding” – neuronal microcircuits can learn from sequences as they unfold. The theory is derived from a physics-inspired, energy-based formulation in which learning corresponds to reducing an internal “energy” that reflects how wrong the network’s output is. From this principle, the researchers derive local neuronal dynamics and synaptic learning rules that closely approximate backpropagation through space and time.

Crucially, these results not only provide a better understanding of learning in the brain, but also a blueprint for improving artificial systems by taking inspiration from their biological archetype. Conventional computing architectures are plagued by the infamous von Neumann bottleneck, which refers to the wasteful transport of data required by the separation of compute and memory units. By naturally providing all the required learning signals precisely when and where they are needed, the proposed model circumvents the von Neumann bottleneck, allowing efficient in-memory computing. This can help reduce the massive energy gap between artificial and biological intelligence.

Learning symmetry

The new study also builds on earlier work by the same group, published in Nature Machine Intelligence in 2024, which addressed another long-standing objection to brain-like learning. In artificial networks, learning requires backward signals to precisely mirror forward connections – a requirement known as the “weight transport problem” and long considered incompatible with biology. The earlier study showed that cortical synapses could learn this mirroring locally by exploiting neural noise, a ubiquitous feature of the brain.

Implications for biological and artificial brains

“We believe these results are of interest for the general public for two separate reasons,” says Mihai A. Petrovici, leader of the Bernese team. “First, we now have a strong hypothesis for a better understanding of how our brains are capable of learning. Second, we now have blueprints for more powerful, but also more energy-efficient AI.”

The project combines insights from neuroscience, physics, mathematics and computer science – an interdisciplinary scope achieved by only a small number of research teams worldwide. “Our team has grown as a project partner and core contributor to the Human Brain Project and EBRAINS, and has greatly profited from the highly interdisciplinary nature of these initiatives,” Petrovici explains. “This represents a unique advantage among large-scale neuroscience-related projects.”

The researchers emphasise that this work is only the beginning. “Because these results have implications for both biological and artificial brains, we aim to continue it in both directions”, says Federico Benitez, a co-author of the study. On the neuroscience side, the team is now searching for signatures of their models in brain data, including through a collaboration with the team who developed The Virtual Brain, a simulation platform available via EBRAINS.

“But the greatest impact outside of basic research may come from actually casting these models into silicon,” Petrovici adds. Together with partners at Yale University, the team is working on the design of novel circuits that could implement the model directly in hardware, enabling real-time learning with far lower energy demands than today’s AI systems.

Original Paper

Ellenberger, B., Haider, P., Benitez, F. et al. Backpropagation through space, time and the brain. Nat Commun 17, 66 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66666-z

Related articles

https://www.nature.com/articles/s42256-024-00845-3

https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2021/hash/94cdbdb84e8e1de8a725fa2ed61498a4-Abstract.html

Press contact

press@ebrains.eu

Create an account

EBRAINS is open and free. Sign up now for complete access to our tools and services.