A new study fostered by EBRAINS has demonstrated how networks of spiking nanolasers could emulate a key principle of brain function: to imagine things that we cannot directly perceive by sampling from internal models of the world.

The study, led by scientists from the University of Bern in collaboration with Thales Research & Technology located in the Paris-Saclay campus area, has now been published in Nature Communications. Physical computers based on semiconductor lasers represent some of the most promising candidates for next-generation AI systems, given their envisaged advantages in speed, bandwidth and power consumption compared to conventional electronics. The study demonstrates how advances at the intersection of neuroscience, physics and computer science could lead to new forms of artificial intelligence.

An essential property of the human brain is its ability to construct a world model – an internal picture of what exists beyond our immediate sensory input. Even when our vision is focused on a screen, we remain aware of the room around us, and we can easily imagine what is hidden from view. Importantly, this model is probabilistic. When we see a swimmer, for example, we may only see the head and shoulders, but we can imagine many plausible positions of the body underwater, while ruling out impossible ones. In statistics, this process is known as Bayesian inference: what is the state of something that we cannot observe, given the state of something that I can observe and my previous knowledge about the world?

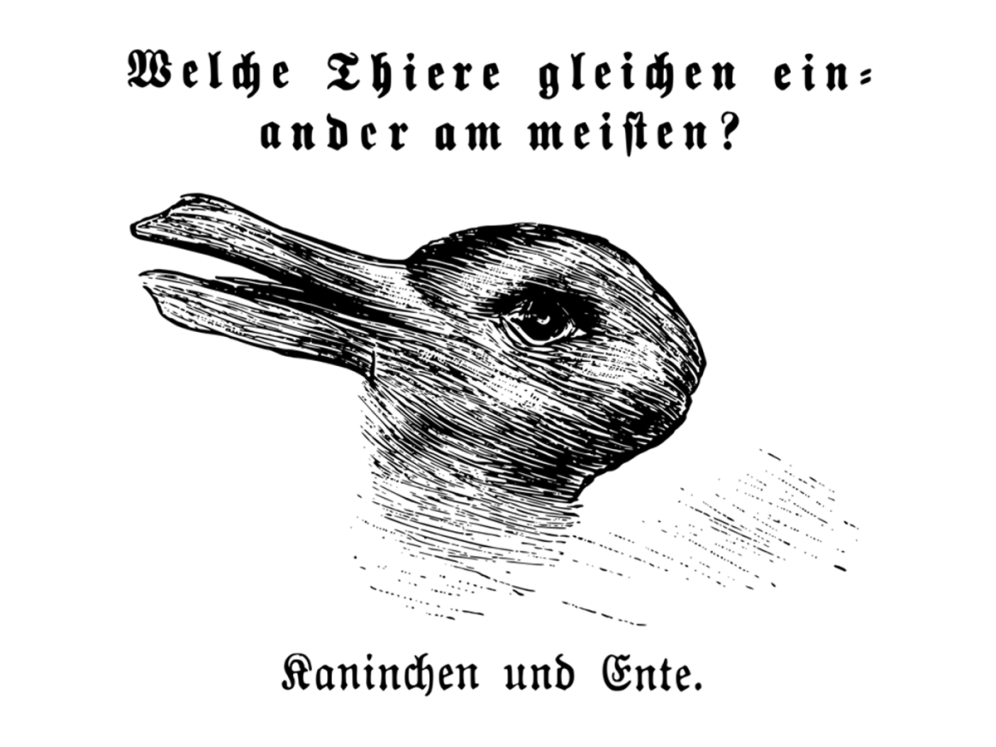

Rather than representing all possibilities at once, the brain appears to sample from this probability distribution. One example is the rabbit-duck illusion (see below): you can see either a rabbit or a duck, but never both simultaneously. “You are never thinking of the full distribution”, Ivan Boikov, a researcher at Thales Research & Technology and one of the authors explains, “but rather drawing samples from it, one at a time.”

At the microscopic level, this sampling behaviour is closely linked to how neurons communicate. Neurons in the neocortex don’t have continuous outputs; instead, they fire action potentials – short electric flashes that propagate to their neighbours. Because the visual cortex is topographically organised, groups of spiking neurons can literally trace out image shapes – such as the contour of the swimmer’s legs underwater, one posture at a time.

From neurons to nanolasers

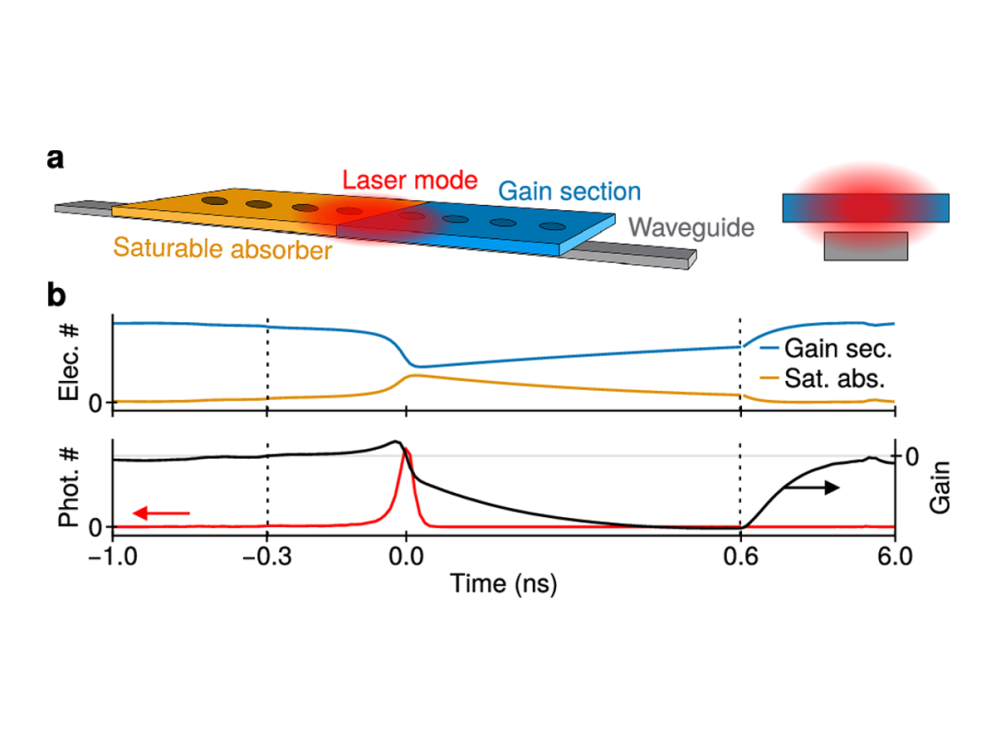

Inspired by this mechanism, the researchers asked whether artificial spiking networks could be built to sample world models in the same way, but much faster. “By replacing the biology of cells with the physics of semiconductors, we can make their dynamics much, much faster,” says co-author Alfredo de Rossi (Thales Research & Technology).

“In this project, we considered semiconductor nanolasers. We have shown in simulations that, using a particular configuration of materials, we can build a network of such nanolasers that can learn and sample from a world model just like the brain does,” he explains.

Such systems could operate on timescales of tens of picoseconds, compared to miliseconds in the brain – hundreds of millions of times faster.

These nanolasers can spike, and spikes can be used for sampling. In their model, networks of nanolasers learn a probabilistic representation of their environment and generate samples from it, closely mirroring how the brain imagines unseen parts of the world.

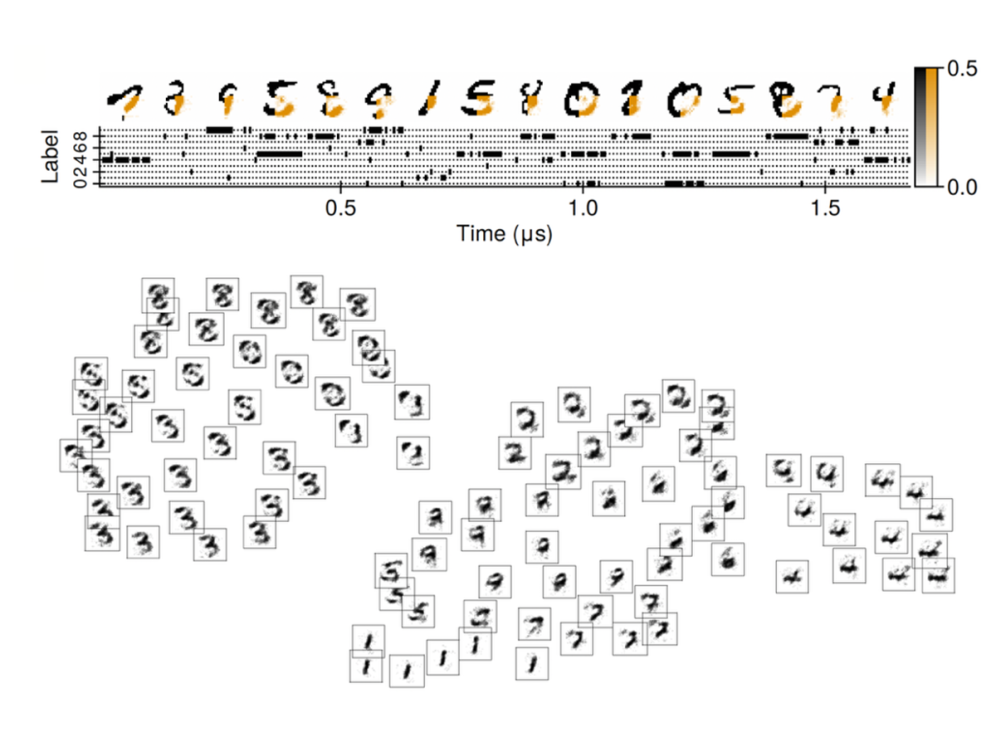

In one demonstration, the network was trained on handwritten digits. When shown only partial information – some pixels while others were hidden – it generated complete digits consistent with the input, imagining threes or zeroes but never implausible alternatives. When unconstrained, the network freely “dreamed” of all possible digits, much like the human brain does during sleep (see below).

Precise spike timing

The question of how spiking networks can learn is a broader one. In this current work, the researchers have used a probabilistic model and training algorithm. But in some cases, a very precise timing of individual spikes is needed. “This is, for example, how our brain encodes information about our tactile sense and the texture or movement of tactile stimuli,” Mihai A. Petrovici, researcher at University of Bern and one of the authors of the study, explains. In principle, researchers could use spike timing to represent any kind of information (e.g., visual, hearing or tactile) on artificial spiking networks. But learning precise spike timing in deep spiking networks poses a challenge.

To add to the challenge, spike timing (in biological and artificial networks) depends not only on the strength of the synapses connecting the neurons but also on the time (or delay) that spikes need to travel between neurons. In a recent related study, published in Nature Communications, the researchers developed a learning algorithm that is an exact replica of classical error backpropagation – the backbone of modern AI – but based purely on spike times.

“We have demonstrated it on the BrainScaleS-2 neuromorphic chip developed by our colleagues at the Heidelberg University,” Petrovici says. While not quite as fast as the nanolaser version, this mixed-signal chip (containing both analog and digital components) is still “about a thousand times faster than an equally sized piece of brain tissue,” while being extremely energy-efficient. (See: “Fast and energy-efficient neuromorphic deep learning with first-spike times”)

Computing advantages

While the idea of spike-based sampling has already been explored over the past decade, - especially by researchers in the Human Brain Project and later EBRAINS, in collaborations between teams from Bern, Heidelberg, Jülich and Graz (see related publications) – the laser-based version is completely new. “It is remarkable that flashing lasers can work pretty much like flashing neurons in the brain (it’s just exchanging sodium and potassium ions for photons),” says Petrovici. “Beyond the elegance of the symmetry between these two very different systems, computing with light offers great practical advantages over computing with electrons, as our current chips do.” Light can be transmitted with far less energy loss than electrical currents, and multiple signals can coexist at different frequencies without interference, enabling much greater bandwidth. “For these reasons,” the authors explain, “high-speed internet is optical.”

Their study proposes concrete blueprints for chip-scale implementations, opening the door to ultrafast, energy-efficient computing hardware.

Multidisciplinary collaboration

The project grew out of a collaboration between a team of neuroAI researchers at the University of Bern and experts in neuromorphic photonics at Thales Research & Technology in Paris-Saclay. “Once you know that lasers can spike, and you know that spikes can be used for sampling, the story almost writes itself,” the authors say – though making it work required a highly interdisciplinary team.

The work builds on the group’s long-standing research into spike-based sampling and complements recent advances in learning precise spike timing on neuromorphic chips. Together, these results highlight how insights from neuroscience, physics and computer science – fostered by the EBRAINS research infrastructure – can converge to inspire new forms of artificial intelligence.

Read publication:

Ultrafast sampling with spiking nanolasers

Boikov, I.K., de Rossi, A. & Petrovici, M.A. Ultrafast neural sampling with spiking nanolasers. Nature Communications (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66818-1

Related publications

Göltz, J., Weber, J., Kriener, L. et al. DelGrad: exact event-based gradients for training delays and weights on spiking neuromorphic hardware. Nat Commun 16, 8245 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63120-y

Dold, D., Bytschok, I., Kungl, A. F., Baumbach, A., Breitwieser, O., Senn, W., Schemmel, J., Meier, K. and Petrovici, M. A. (2019). Neural Networks 119: 200–213.

Korcsak-Gorzo, A., Müller, M. G., Baumbach, A., Leng, L., Breitwieser, O. J., van Albada, S. J., Senn, W., Meier, K., Legenstein, R. and Petrovici, M. A. (2022). PLOS Computational Biology 18, 3: e1009753.

Petrovici, M. A., Bill, J., Bytschok, I., Schemmel, J. and Meier, K. (2016). Physical Review E 94, 4: 042312.

Press contact

Helen Mendes-Lima (press@ebrains.eu)

Create an account

EBRAINS is open and free. Sign up now for complete access to our tools and services.